| juliajubilada = julia retired |

|

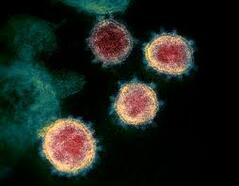

Living with Corona Virus

After watching a Youtube talk by Bayo Akomolafe, I downloaded his "experiment in speculative fabulation" I Corona Virus: Mother, Monster Activist, with amazing illustrations by Jon Marro. Commentary to follow...

This 2016 article on Ebola's ecologies from New Left Review, identifies the ways in which humans messing about with the planet are likely to lead to a pandemic on the scale of the 1918 flu, "with a global reach and high rates of incapacitation and mortality". The authors cite the outbreak of Zaire ebolavirus in West Africa to illustrate the ways in which the development and spread of pathogens can be directly attributable to the many facets of Capitalist agri-business. They provide detailed examples, such as deforestation depriving specific bat species of their natural foraging areas, so they migrate to the massive oil palm plantations with resulting human-bat interaction (bats pissing on the crops, biting and scratching fruit pickers etc). "Nearly every Ebola outbreak to date appears to have been linked to capital-driven shifts in land use, including logging, mining and agriculture, all the way back to Nzara, Sudan in 1976". The culprits are capitalist agri-business, including "…sovereign wealth funds, state-owned enterprises, governments, private equity firms, developers, banks, pension funds and university endowments that financed the development and deforestation which led to disease emergence in the first place".

(*they use the term stochasticity a lot, which means randomness)

Lockdown has encouraged me to discover books in the category "I'm going to read/re-read this some day" that have sat on my shelves for decades. For example:

Camus’ The Plague (click title to download the whole book pdf) Pretty soon I realised why I never got past the first chapters 50 years ago. The are no women – apart from frail wives and patient, self-deprecating mothers. Projections of a masculine primal need for solace and affirmation. * But now I persevered through this prescient tale of warning signs ignored, gruesome symptoms and painful deaths, ever-increasing numbers of dying and dead, lock-down, food shortages, profiteering and fear. Towards the end of the book there’s a conversation between the central character, Dr Rieux and Tarrou, an enigmatic outsider who had only just arrived in the town when the plague struck. Tarrou tells Rieux that when he was seventeen, his father, a Director of Public Prosecutions, invited his son to come and hear him speak in court. Having given little thought to his father’s job, the young man was suddenly brought face to face with the humanity of the “defendant”. While his father urged the jury to impose “the supreme penalty”, Tarrou realised “…they were set on killing that living man, and an uprush of some elemental instinct, like a wave, had swept me to his side”.

Tarrou subsequently left home and embarked on a lifelong campaign against capital punishment. He understood that the existing social order was based on the death penalty, so his task was to join with others to change the social order. He tells Rieux that he wasn’t always able to argue against those who maintained that “… these few deaths were inevitable for the building up of a new world in which murder would cease to be”. But then he witnessed an execution by firing squad, and was moved once again by his affinity with the victim, so that, “… thus I came to understand that I, anyhow, had had plague through all those long years in which, paradoxically enough, I'd believed with all my soul that I was fighting it. I learned that I had had an indirect hand in the deaths of thousands of people; that I'd even brought about their deaths by approving of acts and principles which could only end that way”.

Simply by being human, and living in a society that’s complicit in the murder of other humans (and aren’t we all, when we consider the military-industrial complex that underpins our economy and our material well-being?), since”… we can't stir a finger in this world without the risk of bringing death to somebody… I have realized that we all have plague, and I have lost my peace”.

He concludes, “And I know, too, that we must keep endless watch on ourselves lest in a careless moment we breathe in somebody's face and fasten the infection on him. What's natural is the microbe. All the rest, health, integrity, purity (if you like), is a product of the human will, of a vigilance that must never falter. The good man, the man who infects hardly anyone, is the man who has the fewest lapses of attention. And it needs tremendous will-power, a never ending tension of the mind, to avoid such lapses. Yes, Rieux, it's a wearying business, being plague-stricken. But it's still more wearying to refuse to be it. That's why everybody in the world today looks so tired; everyone is more or less sick of plague. But that is also why some of us, those who want to get the plague out of their systems, feel such desperate weariness, a weariness from which nothing remains to set us free except death”.

______________________________________________________________________________

*Interesting to reflect on the question of the difference between an essentially masculine perspective and the innocent (ignorant?) assumption that masculine pronouns include all genders (“Man breastfeeds his young”?). I’m reminded of Jean Grimshaw’s feminist critique of classical European philosophy. In her book, Feminist Philosophers, she distinguishes between those men whose ideas could include women and those whose whole philosophy rests on the notion that women don’t really count as rational members of human society. When his friend dies, Camus remarks that the doctor “… had a feeling that no peace was possible to him henceforth, any more than there can be an armistice for a mother bereaved of her son or for a man who buries his friend”. Of course you could substitute woman/friend, father/daughter but the profoundly gendered experience of such bereavements is something that Juliet Mitchell explores in her study of sibling attachment (a relationship neglected by Freud) in her book about gender and hysteria, Mad Men and Medusas.

This 2016 article on Ebola's ecologies from New Left Review, identifies the ways in which humans messing about with the planet are likely to lead to a pandemic on the scale of the 1918 flu, "with a global reach and high rates of incapacitation and mortality". The authors cite the outbreak of Zaire ebolavirus in West Africa to illustrate the ways in which the development and spread of pathogens can be directly attributable to the many facets of Capitalist agri-business. They provide detailed examples, such as deforestation depriving specific bat species of their natural foraging areas, so they migrate to the massive oil palm plantations with resulting human-bat interaction (bats pissing on the crops, biting and scratching fruit pickers etc). "Nearly every Ebola outbreak to date appears to have been linked to capital-driven shifts in land use, including logging, mining and agriculture, all the way back to Nzara, Sudan in 1976". The culprits are capitalist agri-business, including "…sovereign wealth funds, state-owned enterprises, governments, private equity firms, developers, banks, pension funds and university endowments that financed the development and deforestation which led to disease emergence in the first place".

(*they use the term stochasticity a lot, which means randomness)

Lockdown has encouraged me to discover books in the category "I'm going to read/re-read this some day" that have sat on my shelves for decades. For example:

Camus’ The Plague (click title to download the whole book pdf) Pretty soon I realised why I never got past the first chapters 50 years ago. The are no women – apart from frail wives and patient, self-deprecating mothers. Projections of a masculine primal need for solace and affirmation. * But now I persevered through this prescient tale of warning signs ignored, gruesome symptoms and painful deaths, ever-increasing numbers of dying and dead, lock-down, food shortages, profiteering and fear. Towards the end of the book there’s a conversation between the central character, Dr Rieux and Tarrou, an enigmatic outsider who had only just arrived in the town when the plague struck. Tarrou tells Rieux that when he was seventeen, his father, a Director of Public Prosecutions, invited his son to come and hear him speak in court. Having given little thought to his father’s job, the young man was suddenly brought face to face with the humanity of the “defendant”. While his father urged the jury to impose “the supreme penalty”, Tarrou realised “…they were set on killing that living man, and an uprush of some elemental instinct, like a wave, had swept me to his side”.

Tarrou subsequently left home and embarked on a lifelong campaign against capital punishment. He understood that the existing social order was based on the death penalty, so his task was to join with others to change the social order. He tells Rieux that he wasn’t always able to argue against those who maintained that “… these few deaths were inevitable for the building up of a new world in which murder would cease to be”. But then he witnessed an execution by firing squad, and was moved once again by his affinity with the victim, so that, “… thus I came to understand that I, anyhow, had had plague through all those long years in which, paradoxically enough, I'd believed with all my soul that I was fighting it. I learned that I had had an indirect hand in the deaths of thousands of people; that I'd even brought about their deaths by approving of acts and principles which could only end that way”.

Simply by being human, and living in a society that’s complicit in the murder of other humans (and aren’t we all, when we consider the military-industrial complex that underpins our economy and our material well-being?), since”… we can't stir a finger in this world without the risk of bringing death to somebody… I have realized that we all have plague, and I have lost my peace”.

He concludes, “And I know, too, that we must keep endless watch on ourselves lest in a careless moment we breathe in somebody's face and fasten the infection on him. What's natural is the microbe. All the rest, health, integrity, purity (if you like), is a product of the human will, of a vigilance that must never falter. The good man, the man who infects hardly anyone, is the man who has the fewest lapses of attention. And it needs tremendous will-power, a never ending tension of the mind, to avoid such lapses. Yes, Rieux, it's a wearying business, being plague-stricken. But it's still more wearying to refuse to be it. That's why everybody in the world today looks so tired; everyone is more or less sick of plague. But that is also why some of us, those who want to get the plague out of their systems, feel such desperate weariness, a weariness from which nothing remains to set us free except death”.

______________________________________________________________________________

*Interesting to reflect on the question of the difference between an essentially masculine perspective and the innocent (ignorant?) assumption that masculine pronouns include all genders (“Man breastfeeds his young”?). I’m reminded of Jean Grimshaw’s feminist critique of classical European philosophy. In her book, Feminist Philosophers, she distinguishes between those men whose ideas could include women and those whose whole philosophy rests on the notion that women don’t really count as rational members of human society. When his friend dies, Camus remarks that the doctor “… had a feeling that no peace was possible to him henceforth, any more than there can be an armistice for a mother bereaved of her son or for a man who buries his friend”. Of course you could substitute woman/friend, father/daughter but the profoundly gendered experience of such bereavements is something that Juliet Mitchell explores in her study of sibling attachment (a relationship neglected by Freud) in her book about gender and hysteria, Mad Men and Medusas.