| juliajubilada = julia retired |

|

I wrote this critique for undergraduate youth workers as part of a distance learning package. If you want to follow up references to other units (eg (CLD3 etc), ask questions or comment on this paper, please contact me.

Humanism, as a belief in the central importance of human beings, is associated with the break from the authority of the church that came to be known as the Enlightenment. As I explained in our discussion of the Self (CLD3 Unit 1, Item 3), a humanistic understanding of the self assumes a universal and shared vision of what it means for people to “realise their humanity”. I have also argued (Clarke, 2002) that this vision of what it means to be human, the ideal of an autonomous, self-contained individual, is based on a western, and particularly masculine, ideal of humanity.

In this item I want to trace the origins of humanistic learning theories from the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, through the humanistic psychology of Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers to theories of adult learning that focus on individual growth and self-directed learning. This will be a critical account, challenging some of the basic assumptions which underpin the practices of informal education. My reason for drawing your attention to the selfish and elitist aspects of these ideas is because I am concerned that an emphasis on personal growth can serve to support an ideology of individualism and greed that perpetuates the inequality, oppression and injustices of global capitalism. This does not mean rejecting the valuable lessons that can be taken from ideas about human potential, about the importance of emotions in learning and about valuing individuals. I offer this critique as an alternative perspective with the aim of encouraging you to pose questions about your own responsibility, as educator, or “facilitator” of learning, to consider whether and how your educational practice can make a difference to the kind of society we live in.

Nietzsche and Foucault: science, power and knowledge

While the Enlightenment represented the triumph of reason and science over religious dogma, the German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, argued that religion, science and rational knowledge are all expressions of man’s innate desire for power. Certainly, scientific methods can be regarded as a set of rituals and procedures which confer an almost god-like authority on our claims that something is “true”. As an undergraduate, one of the first learning outcomes you are required to demonstrate is the ability to distinguish “fact” from “opinion”. Of course it’s important that you are aware of the interests, desires, assumptions and prejudices that lead you to form opinions, and these can be weighed against evidence, or “facts” which challenge you to defend these opinions through rational argument. But what is a “fact”?

Facts tend to be statements about the world supported by evidence. The most powerful evidence is that which claims to be derived from scientific methods like questionnaire surveys, controlled experiments, structured observations, and the conclusions drawn from these. The status of “facts” depends on the idea that personal desires, philosophical assumptions and political interests can be eliminated from scientific research. But somebody (usually somebody with the power and resources to gain funding for the research), chooses what to observe, how to conduct the research, what (or who) to include or exclude, and which conclusions to publish.

Nietzsche argued that scientific method and rational argument are masks that simply hide man’s “will to power”, which is primarily a physical, embodied desire. There are plenty of examples of scientific “facts” being produced in the interests of powerful groups. See, for example, George Monbiot’s (2006) account of the vast sums of money spent on the publication of persuasive “scientific facts” to justify current levels of energy consumption.

Which individuals or groups might have an interest in producing facts about:

. distribution of income among men and women in the UK

. the effects of cannabis smoking on the brain

. numbers of immigrants to the UK in the past year

. global warming.

Nietzsche’s recognition of the self-deception involved in claims to rationality and truth has made an important and useful contribution to postmodern, postcolonial and feminist thinking about power and knowledge. The French philosopher, Michel Foucault, drew on Nietzsche’s ideas for his own analysis of the relationship between knowledge and power in discourse, which I hope you will read about in later units. However, while pointing to the desires that motivate the search for knowledge, Nietzsche argued for a re-connection of mind and body that would enable Man to indulge his passions and rise above his fruitless quest for abstraction and universal truths. He likened the pursuit of truth to the courting of an elusive woman and regarded those who engaged in such a deluded quest with a savage contempt. He scorned humanitarian values and democratic pretensions as symptoms of common subjection to Judeao-Christian morality. The “virtues” of kindness, caring and sympathy cannot be valued, according to Nietzsche, when they rely on the weakness and self-denial of duty, humility or religious obligation. He advocated a form of self-indulgent elitism based on a desire for self-affirmation which could only ever be achieved by a noble few. For example:

“A man who says, “I like that, I take it for my own, and mean to guard and protect it from everyone”; a man who can conduct a case, carry out a resolution, remain true to an opinion, keep hold of a woman, punish and overthrow insolence; a man who has indignation and his sword, and to whom the weak, the suffering, the oppressed, and even the animals willingly submit and naturally belong; in short, a man who is master by nature – when such a man has sympathy, well! That sympathy has value” (Nietzsche, 1914:259)

This idea of the elite individual, liberated from the constraints of social responsibility and from any obligation to care for others, is represented in Abraham Maslow’s notion of “self-actualisation” – a founding principle of humanistic psychology.

Maslow’s hierarchy: who needs self-actualisation?

The North American psychologist, Abraham Maslow, is represented for his followers by a belief that all human beings are capable of reaching a state of creativity and fulfilment which constitutes an on-going process of self-actualisation. This process depends on a hierarchy of needs being met from basic safety, through love and “belongingness”, self-esteem, needing to know and understand, appreciation of art and beauty and ultimately self-actualisation. Common criticisms of this model are that it is not based on any kind of systematic research among ordinary people, and that there is little evidence to support this hierarchical view. It may be helpful to note that, for example, children who are cold or hungry will probably find it hard to concentrate on school lessons. So Maslow’s hierarchy can be used to argue for breakfast clubs and warm classrooms. But there are countless examples of hungry or homeless people who are capable of forming loving relationships, learning what they want to learn and appreciating art and music. There is a far more fundamental problem with Maslow’s hierarchy, however, and this lies in his vision of an ideal society in which a small elite of “self-actualised” people are deemed superior because of their ability to detach themselves from the needs, interests and desires of others.

This vision of the superior, self-actualised individual is very close to Nietzsche’s description of the master,

“Under good conditions the superior person is totally freed, or anyway more freed, to enjoy himself completely, to express himself as he pleases, to pursue his own selfish ends without worrying about anybody else, or feeling any guilt or obligation to anybody else, in the full confidence that everybody will benefit by his being fully himself and pursuing his own selfish ends” (Maslow, 1965:105)

Following the publication of his first papers in the late 1940s, Maslow’s ideas were welcomed by a group of social psychologists led by Kurt Lewin who had been working with training groups, later known as “T Groups”, to explore democratic styles of leadership. At the same time, Carl Rogers was researching his own practice as a psychotherapist along lines which were much closer to Maslow’s view of human nature than to the contemporary orthodoxies of behaviourism or psychoanalysis. In a departure from the emphasis on social control in behaviourism and the focus on the darker side of the unconscious in psychoanalysis, Carl Rogers, along with Maslow, Lewin, Herbert Marcuse and others, founded the Journal of Humanistic Psychology in 1961.

Carl Rogers: is this the person you want to become?

Carl Rogers came to psychology via agriculture, theology and work with children with behavioural problems. Rogers’ view of human development is based on the idea that we are born knowing what is good for us. The infant’s preference for food, warmth and security and desire to explore and investigate her world are totally compatible with the conditions which promote healthy growth. He believed that, if we haven’t lost touch with what we really want and need, then our choices will be directed towards things which promote our growth and well-being. During the socialisation process, however, adult responses to anti-social behaviour tend to induce guilt, resentment and repression. This leads us to mistrust our own organismic valuing processes which promote emotional growth and self-esteem. In order to attract loving and accepting responses from others we will only express those aspects of ourselves which we think others will value. This means suppressing, and consequently losing touch with, the full complexity of our true feelings and thus our real selves.

Rogers shared Maslow’s ideal of the emotionally self-sufficient adult who is in touch with his desires and feels free to express them. Achieving this state is what Carl Rogers describes as “becoming a person”. While this involves freeing ourselves from the social and cultural influences that tell us who and how to be, it also seems to include freeing oneself from being too concerned about the effect on other people of choosing to follow your own desires. For example:

“I think the ideal situation is when one can tell the partner: ‘I need and I owe it to myself to experience this other relationship now. I’m hearing your hurt, your jealousy, your fear, your anger; I do not like to receive them, but they are a consequence of the choice I’m making, and I love you enough to want to be available to work through them with you. If I decide not to have this other experience, it is because I choose to do so and not because I let you stop me. In that way I won’t feel resentful of you and I won’t punish you for my lack of courage in making my choices and being responsible for the consequences”. This is a mature kind of striving for both independence and richness” (Rogers, 1978: 55-6)

Can you imagine trying to justify this kind of self-serving behaviour by saying that you need and owe it to yourself to experience whatever it is you want? Or, if somebody spoke like this to you when you’ve been

hurt by their behaviour, how would you respond to their offer to “be available to work through” your feelings?

It may be argued that we should not judge Rogers’ attempt to justify an “open marriage” without taking account of the social climate in the 1960s during what has sometimes been represented as a time of “sexual revolution”. Of course, we should always consider ideas in their historical and cultural location. This is precisely why we should also be extremely wary of prescriptions for the kind of person which all individuals, regardless of time, place and cultural context, can or should aspire to become. Here, I should acknowledge that my critique of humanistic psychology is influenced by my personal experience as a young woman during the late 1960s and as a mother in the early 1970s. The language of the humanistic “Encounter Group” provided men, and women too, with a powerful coercive weapon.

When people talk about their “needs”, they transform a wish or desire into something that demands to be satisfied. If you obstruct or resist the satisfaction of these “needs” or desires, you can be accused of being “repressed” or “hung-up” on internalised social values like duty and responsibility from which you should be encouraged to break free in order to discover your inner self.

Much of the criticism of Nietzsche, Maslow and Rogers in this introduction to humanistic learning theories has been taken from the feminist perspectives explored by Jean Grimshaw in the chapter that is included as the first Reading to accompany this Item (CLD3 2.4a). She concludes this chapter with a quote from Naomi Scheman (1983), who points out that

“There is every reason to react with alarm to the prospect of a world filled with self-actualising persons pulling their own strings, capable of guiltlessly saying ‘no’ to anyone about anything, and freely choosing when to begin and end their relationships. It is hard to see how, in such a world, children could be raised, the sick or disturbed could be cared for, or people could know each other through their lives and grow old together” (cited in Grimshaw, 1986: 161).

Other criticisms of humanistic psychology and the personal growth movement point to the lack of any structural analysis of inequality and exploitation in a capitalist society. The personal growth movement was described by Barry Richards as “...the ideology of personal adjustment as opposed to political commitment and organisation, of self-fulfilment as opposed to social change, and of serving self and not serving others” (Richards, 1974:4). While agreeing with this criticism, I also recognise the value of humanistic psychology’s focus on emotional processes in learning, which are often neglected or ignored in the drive to demonstrate achievement against pre-determined learning outcomes.

The educator as facilitator of person-centred learning

One explanation for the enormous influence of Carl Rogers’ work is that his emphasis on non-directive facilitation can be taken up by therapists, counsellors, youth workers, informal educators, human resource developers, in fact anybody who wants to play a role in supporting learning without being a teacher. Although Rogers claimed that the aim of a person-centred approach is democracy and co-operation, the primary focus is on enabling individuals to pursue their own interests. In education for any age group, a student-centred curriculum starts from the innate desire to learn and resolve the problems which are perceived as real by the learners. Rogers offers no clear role for the facilitator in formulating a curriculum or guiding choices but suggests that the learner-centred facilitator will, by definition, be secure enough in her own self-worth to be able to base her practice on the primary value of trusting and valuing the learner.

The second reading with this item comprises extracts from the 3rd edition of Freedom to Learn (CLD3 2.4b). Rogers’ critique of conventional education in this extract echoes that of Paulo Freire’s (1972) view of “banking education”. He describes the top down “mug and jug” model in which the learners are regarded as empty vessels to be filled with knowledge, and contrasts this with a person-centred approach for which the only precondition is trust:

“A leader or a person who is perceived as an authority figure in the situation is sufficiently secure within herself and in relationships with others to experience an essential trust in the capacity of others to think for themselves, to learn for themselves. She regards human beings as trustworthy organisms….” (Rogers, 1994:212)

Through his work as a therapist, Rogers maintained that there were a particular set of attitudinal qualities which a therapist or educator should develop in order to facilitate significant learning. These “core conditions” comprise:

If you are interested in Carl Rogers’ work, then you would do well to read Freedom to Learn, for yourself. It’s readily available in libraries, and it is accessible and easy to read, with plenty of stories from educational practice, mainly in North American schools. If you prefer to read a summary, you can download the article by Smith, (1997, 2004), who offers a brief critical discussion of the “core conditions” outlined above. In this summary, Mark Smith identifies a problem for informal educators with Rogers’ account of empathy as the ability to step into the other person’s shoes:

“…the task is not so much to enter and understand the other person, as to work for understanding and commitment. This is not achieved simply by getting into the shoes of another. Conversation involves working to bring together the insights and questions of the different parties; it entails the fusion of a number of perspectives, not the entering into of one…”

I would add to this concern, a lack of acknowledgement in these “core conditions” of the unequal power relations in most educational encounters, and the lack of attention to the group processes in which the facilitator’s task may include that of mediating between conflicting interests.

Read through the eight aspects of a “person-centred mode” which are summarised in the extracts from Freedom to Learn (CLD3 2.4b) and think about the following questions in relation to your own experience as a student.

Rogers does not attempt to analyse the structural issues that might help to illuminate these questions and suggest collective strategies for change. For example, professional qualifications serve a gate-keeping function in regulating who can call themselves a teacher, doctor, lawyer, counsellor or youth worker. Later in the book, Rogers describes various attempts to change educational institutions by bringing together staff and students at all levels of the hierarchy. Through the process of group discussion which Rogers and his colleagues initiated, the institutions were able to adopt more co-operative and democratic approaches to their work. But these institutions failed to sustain their internal democracy due to the interests of powerful groups in the wider society.

A school whose Black students and parents began to work together in democratic ways posed too great a threat to the existing political control of the surrounding White community. A Catholic college was closed after the Vatican discovered that nuns were making their own rules. Rogers acknowledged that real participatory democracy is an enormously challenging process. In his analysis of the “Reasons for Impermanence” of so many democratic and person-centred projects, Rogers stresses the lack of experience of this process among bureaucrats and administrators and fear of losing control which accounts for their hostility towards person-centred organisations.

The “fully functioning person” as an educational goal

I would argue that another “reason for impermanence” of these projects is that it’s just not enough to focus exclusively on process without offering tools for analysis and strategies for action. The goal of education, for Rogers is simply to promote the development of the “Fully Functioning Person” who will be equipped to continue striving for a more human world:

The only man who is educated is the man who has learned how to learn; the man who has learned how to adapt and change; the man who has realised that no knowledge is secure, that only the process of seeking knowledge gives a basis for security. Changingness, a reliance on process rather than upon static knowledge, is the only thing that makes any sense as a goal for education in the modern world. [Rogers,1983:120]

The modern world to which Rogers refers has become one in which it is very much in the interests of free-market enterprise to foster qualities and processes of “changingness” and flexibility (see, for example, Klein, 2008). The flexible movement of capital and labour, through flexible organisations which can adapt their products and services to gain advantage in rapidly changing markets, is supported by a flexible workforce of self-directing, “enterprising” individuals (Du Gay, 1996). A flexible, student-centred learning process is ideal for the production of such a workforce, willing to work flexible hours for flexible pay, to be downsized, upskilled or relocated in the service of the global corporation. Humanistic approaches to professional development and management training have provided an effective means for increasing productivity, but there is little evidence that this approach has led to more equal opportunities for participation in significant decision-making within or between the organisations of the workplace, the school or the public services.

When I began working in adult and community education in the 1970s, I welcomed Carl Rogers’ emphasis on the need to tune in to the experiences, interests and desires of learners in order to engage them fully in the learning process. This aspect of student-centred learning is influenced by John Dewey and shared by Paulo Freire. In the work of both Dewey and Rogers, however, the lack of attention to the role of the teacher or educator became problematic when political changes in the 1980s resulted in a shift in the meaning of student-centred learning. In the policy discourses of flexible learning, cost-effectiveness and the incorporation of business models into public sector organisations, student centred learning positioned the student as a customer in a supermarket of educational commodities or outcomes. The behaviourist framework of NVQs was presented in the language of freedom and individual choice (Jessup, 1991). The role of the educator as facilitator, in what Michael Collins (1994) described as a “cult of efficiency” was to offer advice and guidance to the bewildered customer in their choice of educational products (Clarke, 1993). In the context of adult education, Collins attributed this change to the influence of humanistic psychology on the work of Malcolm Knowles and the theory of andragogy.

Andragogy: a humanistic model for adult education?

We referred to the concept of andragogy in item 2 of this unit with reference to debates about the distinctive features of adult learners. In unit 1, item 3, we looked at changing ideas about individual and collective identities and contrasted the Enlightenment view of the “monological self”, with a Postmodern understanding of the “dialogical” or social self. I pointed out that:

Educational goals of autonomy and fulfilment, Erikson’s view of the development of individual identity, Maslow’s idea of self-actualisation, Carl Rogers’ notion of being “fully human” and Malcolm Knowles’ theory of andragogy are all rooted in modernist conceptions of the self (Clarke, 2010:2).

The problem with all these theories is that they don’t recognise and take account of the diverse experiences and social situations in which people may be and become adult human beings. Andragogy is a term used by Malcolm Knowles to define a theory of adult learning based on a particular set of assumptions about how adults learn. I hope that our discussion of Behaviourist and Humanist learning theories in this unit has equipped you with a critical eye to make your own evaluation of the theoretical basis for the theory of andragogy. I also hope that the items and Readings in unit 1: Critical theory for Critical Practice has suggested some alternative ideas and frameworks to guide an educational practice for social justice. In the final Reading with this item (CLD3 2.4c) Mark Smith explores Knowles’ ideas in relation to the work of both Carl Rogers and the pioneering adult educator, Eduard Lindeman.

Once again, Smith presents the arguments for and against Knowles’ claims, based on research conducted among mainly well-educated adults in North America, that all adults share particular characteristics as learners. For example:

… as an individual matures, his need and capacity to be self-directing, to utilise his experience in learning, to identify his own readiness to learn, and to organise his learning around life problems, increases steadily from infancy to pre-adolescence, and then increases rapidly during adolescence. (1978: 54)

This may certainly be true of some adults, in some situations. It may also be true of some children and young people in some situations. But the ways in which, and the extent to which, anyone directs their own learning, or uses their own experience for learning, depends on what kind of learning is going on, for what purpose, with whom and in what context. This is why it’s so important to consider the social context in which learning takes place, the cultural experiences, assumptions and expectations, and the relationship between educators and learners. We concluded item 2 with some questions about what an adult needs to learn in order to become an “authentic” self-directed learner. In the accompanying Reading, Stephen Brookfield points to the limitations of the humanistic concept of the self:

The self in a self-directed learning project is not an autonomous, innocent self, contentedly floating free from cultural influences. It has not sprung fully formed out of a political vacuum. It is, rather, an embedded self, a self whose instincts, values, needs and beliefs have been shaped by the surrounding culture. As such, it is a self that reflects the constraints and contradictions, as well as the liberatory possibilities, of that culture. The most critically sophisticated and reflective adults cannot escape their own autobiographies. Only with a great deal of effort and a lot of assistance from others can we become aware of how what we think are our own wholly altruistic impulses, free from any bias of race, gender or class, actually end up reinforcing repressive structures. Hence, an important aspect of a fully adult self-directed learning project should be a reflective awareness of how one’s desires and needs have been culturally formed and of how cultural factors can convince one to pursue learning projects that are against one’s own best interests (Brookfield 1994:7).

The final item in this unit will explore theories of learning which recognise the central importance of social context and collective learning processes.

References

Brookfield, S. (1994) Self-directed learning, CLD3 2.2d YMCA George Williams College.

Clarke, J. (1993) Unpacking student-centred learning, unpublished MA dissertation, Southampton University (available from the George Williams College library).

Clarke, J. (2002) Deconstructing Domestication: women’s experience and the goals of critical pedagogy in Harrison, Roger et al (eds) Supporting lifelong learning Volume 1: perspectives on learning, Routledge/Falmer (This chapter is included among the readings for CLD3 Unit 1, Item 2).

Collins, M. (1994) Adult Education as Vocation, Routledge.

Du Gay, P. (1996) Consumption and identity at work. London: Sage.

Freire, P. (1972), Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Penguin.

Grimshaw, J. (1986) Feminist Philosophers: women’s perspectives on philosophical traditions, Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Jessup, G. (1991) Outcomes: NVQs and the emerging model of education and training, Routledge.

Klein, N. (2008) The Shock Doctrine:The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, Random House.

Monbiot, G. (2006) Heat: How to Stop the Planet Burning, Allen Lane. Richards, B. Against Humanistic Psychology in Self and Society, 2, 1974. Rogers, C. (1978) Carl Rodgers on Personal Power: Inner Strength and Its Revolutionary Impact, Constable, London.

Rogers, C. and Freiberg, H. J. (1994) Freedom to Learn (3rd edition) Macmillan.

Smith, M. K. (1997, 2004) ‘Carl Rogers and informal education’, the encyclopaedia of informal education. [www.infed.org/thinkers/et-rogers.htm.

Images

(These links are to images used in the pdf version)

Maslow’s hierarchy http://idlichutney.blogspot.com/2008/12/i-need-to-know.html

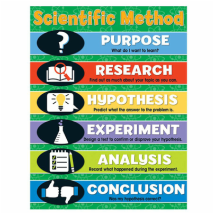

Scientific inquiry http://ez002.k12.sd.us/Introduction%20Science.htm

Encounter group http://www.searchviews.com/wp-content/themes/clean-copy-full-3-column-1/images/group-therapy.jpg

Humanism, as a belief in the central importance of human beings, is associated with the break from the authority of the church that came to be known as the Enlightenment. As I explained in our discussion of the Self (CLD3 Unit 1, Item 3), a humanistic understanding of the self assumes a universal and shared vision of what it means for people to “realise their humanity”. I have also argued (Clarke, 2002) that this vision of what it means to be human, the ideal of an autonomous, self-contained individual, is based on a western, and particularly masculine, ideal of humanity.

In this item I want to trace the origins of humanistic learning theories from the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, through the humanistic psychology of Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers to theories of adult learning that focus on individual growth and self-directed learning. This will be a critical account, challenging some of the basic assumptions which underpin the practices of informal education. My reason for drawing your attention to the selfish and elitist aspects of these ideas is because I am concerned that an emphasis on personal growth can serve to support an ideology of individualism and greed that perpetuates the inequality, oppression and injustices of global capitalism. This does not mean rejecting the valuable lessons that can be taken from ideas about human potential, about the importance of emotions in learning and about valuing individuals. I offer this critique as an alternative perspective with the aim of encouraging you to pose questions about your own responsibility, as educator, or “facilitator” of learning, to consider whether and how your educational practice can make a difference to the kind of society we live in.

Nietzsche and Foucault: science, power and knowledge

While the Enlightenment represented the triumph of reason and science over religious dogma, the German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, argued that religion, science and rational knowledge are all expressions of man’s innate desire for power. Certainly, scientific methods can be regarded as a set of rituals and procedures which confer an almost god-like authority on our claims that something is “true”. As an undergraduate, one of the first learning outcomes you are required to demonstrate is the ability to distinguish “fact” from “opinion”. Of course it’s important that you are aware of the interests, desires, assumptions and prejudices that lead you to form opinions, and these can be weighed against evidence, or “facts” which challenge you to defend these opinions through rational argument. But what is a “fact”?

Facts tend to be statements about the world supported by evidence. The most powerful evidence is that which claims to be derived from scientific methods like questionnaire surveys, controlled experiments, structured observations, and the conclusions drawn from these. The status of “facts” depends on the idea that personal desires, philosophical assumptions and political interests can be eliminated from scientific research. But somebody (usually somebody with the power and resources to gain funding for the research), chooses what to observe, how to conduct the research, what (or who) to include or exclude, and which conclusions to publish.

Nietzsche argued that scientific method and rational argument are masks that simply hide man’s “will to power”, which is primarily a physical, embodied desire. There are plenty of examples of scientific “facts” being produced in the interests of powerful groups. See, for example, George Monbiot’s (2006) account of the vast sums of money spent on the publication of persuasive “scientific facts” to justify current levels of energy consumption.

Which individuals or groups might have an interest in producing facts about:

. distribution of income among men and women in the UK

. the effects of cannabis smoking on the brain

. numbers of immigrants to the UK in the past year

. global warming.

Nietzsche’s recognition of the self-deception involved in claims to rationality and truth has made an important and useful contribution to postmodern, postcolonial and feminist thinking about power and knowledge. The French philosopher, Michel Foucault, drew on Nietzsche’s ideas for his own analysis of the relationship between knowledge and power in discourse, which I hope you will read about in later units. However, while pointing to the desires that motivate the search for knowledge, Nietzsche argued for a re-connection of mind and body that would enable Man to indulge his passions and rise above his fruitless quest for abstraction and universal truths. He likened the pursuit of truth to the courting of an elusive woman and regarded those who engaged in such a deluded quest with a savage contempt. He scorned humanitarian values and democratic pretensions as symptoms of common subjection to Judeao-Christian morality. The “virtues” of kindness, caring and sympathy cannot be valued, according to Nietzsche, when they rely on the weakness and self-denial of duty, humility or religious obligation. He advocated a form of self-indulgent elitism based on a desire for self-affirmation which could only ever be achieved by a noble few. For example:

“A man who says, “I like that, I take it for my own, and mean to guard and protect it from everyone”; a man who can conduct a case, carry out a resolution, remain true to an opinion, keep hold of a woman, punish and overthrow insolence; a man who has indignation and his sword, and to whom the weak, the suffering, the oppressed, and even the animals willingly submit and naturally belong; in short, a man who is master by nature – when such a man has sympathy, well! That sympathy has value” (Nietzsche, 1914:259)

This idea of the elite individual, liberated from the constraints of social responsibility and from any obligation to care for others, is represented in Abraham Maslow’s notion of “self-actualisation” – a founding principle of humanistic psychology.

Maslow’s hierarchy: who needs self-actualisation?

The North American psychologist, Abraham Maslow, is represented for his followers by a belief that all human beings are capable of reaching a state of creativity and fulfilment which constitutes an on-going process of self-actualisation. This process depends on a hierarchy of needs being met from basic safety, through love and “belongingness”, self-esteem, needing to know and understand, appreciation of art and beauty and ultimately self-actualisation. Common criticisms of this model are that it is not based on any kind of systematic research among ordinary people, and that there is little evidence to support this hierarchical view. It may be helpful to note that, for example, children who are cold or hungry will probably find it hard to concentrate on school lessons. So Maslow’s hierarchy can be used to argue for breakfast clubs and warm classrooms. But there are countless examples of hungry or homeless people who are capable of forming loving relationships, learning what they want to learn and appreciating art and music. There is a far more fundamental problem with Maslow’s hierarchy, however, and this lies in his vision of an ideal society in which a small elite of “self-actualised” people are deemed superior because of their ability to detach themselves from the needs, interests and desires of others.

This vision of the superior, self-actualised individual is very close to Nietzsche’s description of the master,

“Under good conditions the superior person is totally freed, or anyway more freed, to enjoy himself completely, to express himself as he pleases, to pursue his own selfish ends without worrying about anybody else, or feeling any guilt or obligation to anybody else, in the full confidence that everybody will benefit by his being fully himself and pursuing his own selfish ends” (Maslow, 1965:105)

Following the publication of his first papers in the late 1940s, Maslow’s ideas were welcomed by a group of social psychologists led by Kurt Lewin who had been working with training groups, later known as “T Groups”, to explore democratic styles of leadership. At the same time, Carl Rogers was researching his own practice as a psychotherapist along lines which were much closer to Maslow’s view of human nature than to the contemporary orthodoxies of behaviourism or psychoanalysis. In a departure from the emphasis on social control in behaviourism and the focus on the darker side of the unconscious in psychoanalysis, Carl Rogers, along with Maslow, Lewin, Herbert Marcuse and others, founded the Journal of Humanistic Psychology in 1961.

Carl Rogers: is this the person you want to become?

Carl Rogers came to psychology via agriculture, theology and work with children with behavioural problems. Rogers’ view of human development is based on the idea that we are born knowing what is good for us. The infant’s preference for food, warmth and security and desire to explore and investigate her world are totally compatible with the conditions which promote healthy growth. He believed that, if we haven’t lost touch with what we really want and need, then our choices will be directed towards things which promote our growth and well-being. During the socialisation process, however, adult responses to anti-social behaviour tend to induce guilt, resentment and repression. This leads us to mistrust our own organismic valuing processes which promote emotional growth and self-esteem. In order to attract loving and accepting responses from others we will only express those aspects of ourselves which we think others will value. This means suppressing, and consequently losing touch with, the full complexity of our true feelings and thus our real selves.

Rogers shared Maslow’s ideal of the emotionally self-sufficient adult who is in touch with his desires and feels free to express them. Achieving this state is what Carl Rogers describes as “becoming a person”. While this involves freeing ourselves from the social and cultural influences that tell us who and how to be, it also seems to include freeing oneself from being too concerned about the effect on other people of choosing to follow your own desires. For example:

“I think the ideal situation is when one can tell the partner: ‘I need and I owe it to myself to experience this other relationship now. I’m hearing your hurt, your jealousy, your fear, your anger; I do not like to receive them, but they are a consequence of the choice I’m making, and I love you enough to want to be available to work through them with you. If I decide not to have this other experience, it is because I choose to do so and not because I let you stop me. In that way I won’t feel resentful of you and I won’t punish you for my lack of courage in making my choices and being responsible for the consequences”. This is a mature kind of striving for both independence and richness” (Rogers, 1978: 55-6)

Can you imagine trying to justify this kind of self-serving behaviour by saying that you need and owe it to yourself to experience whatever it is you want? Or, if somebody spoke like this to you when you’ve been

hurt by their behaviour, how would you respond to their offer to “be available to work through” your feelings?

It may be argued that we should not judge Rogers’ attempt to justify an “open marriage” without taking account of the social climate in the 1960s during what has sometimes been represented as a time of “sexual revolution”. Of course, we should always consider ideas in their historical and cultural location. This is precisely why we should also be extremely wary of prescriptions for the kind of person which all individuals, regardless of time, place and cultural context, can or should aspire to become. Here, I should acknowledge that my critique of humanistic psychology is influenced by my personal experience as a young woman during the late 1960s and as a mother in the early 1970s. The language of the humanistic “Encounter Group” provided men, and women too, with a powerful coercive weapon.

When people talk about their “needs”, they transform a wish or desire into something that demands to be satisfied. If you obstruct or resist the satisfaction of these “needs” or desires, you can be accused of being “repressed” or “hung-up” on internalised social values like duty and responsibility from which you should be encouraged to break free in order to discover your inner self.

Much of the criticism of Nietzsche, Maslow and Rogers in this introduction to humanistic learning theories has been taken from the feminist perspectives explored by Jean Grimshaw in the chapter that is included as the first Reading to accompany this Item (CLD3 2.4a). She concludes this chapter with a quote from Naomi Scheman (1983), who points out that

“There is every reason to react with alarm to the prospect of a world filled with self-actualising persons pulling their own strings, capable of guiltlessly saying ‘no’ to anyone about anything, and freely choosing when to begin and end their relationships. It is hard to see how, in such a world, children could be raised, the sick or disturbed could be cared for, or people could know each other through their lives and grow old together” (cited in Grimshaw, 1986: 161).

Other criticisms of humanistic psychology and the personal growth movement point to the lack of any structural analysis of inequality and exploitation in a capitalist society. The personal growth movement was described by Barry Richards as “...the ideology of personal adjustment as opposed to political commitment and organisation, of self-fulfilment as opposed to social change, and of serving self and not serving others” (Richards, 1974:4). While agreeing with this criticism, I also recognise the value of humanistic psychology’s focus on emotional processes in learning, which are often neglected or ignored in the drive to demonstrate achievement against pre-determined learning outcomes.

The educator as facilitator of person-centred learning

One explanation for the enormous influence of Carl Rogers’ work is that his emphasis on non-directive facilitation can be taken up by therapists, counsellors, youth workers, informal educators, human resource developers, in fact anybody who wants to play a role in supporting learning without being a teacher. Although Rogers claimed that the aim of a person-centred approach is democracy and co-operation, the primary focus is on enabling individuals to pursue their own interests. In education for any age group, a student-centred curriculum starts from the innate desire to learn and resolve the problems which are perceived as real by the learners. Rogers offers no clear role for the facilitator in formulating a curriculum or guiding choices but suggests that the learner-centred facilitator will, by definition, be secure enough in her own self-worth to be able to base her practice on the primary value of trusting and valuing the learner.

The second reading with this item comprises extracts from the 3rd edition of Freedom to Learn (CLD3 2.4b). Rogers’ critique of conventional education in this extract echoes that of Paulo Freire’s (1972) view of “banking education”. He describes the top down “mug and jug” model in which the learners are regarded as empty vessels to be filled with knowledge, and contrasts this with a person-centred approach for which the only precondition is trust:

“A leader or a person who is perceived as an authority figure in the situation is sufficiently secure within herself and in relationships with others to experience an essential trust in the capacity of others to think for themselves, to learn for themselves. She regards human beings as trustworthy organisms….” (Rogers, 1994:212)

Through his work as a therapist, Rogers maintained that there were a particular set of attitudinal qualities which a therapist or educator should develop in order to facilitate significant learning. These “core conditions” comprise:

- congruence (being one’s “real” self in relation to others)

- empathy (being sensitive to the client/learner’s experience)

- positive regard (the unconditional valuing of and trust in the human organism).

If you are interested in Carl Rogers’ work, then you would do well to read Freedom to Learn, for yourself. It’s readily available in libraries, and it is accessible and easy to read, with plenty of stories from educational practice, mainly in North American schools. If you prefer to read a summary, you can download the article by Smith, (1997, 2004), who offers a brief critical discussion of the “core conditions” outlined above. In this summary, Mark Smith identifies a problem for informal educators with Rogers’ account of empathy as the ability to step into the other person’s shoes:

“…the task is not so much to enter and understand the other person, as to work for understanding and commitment. This is not achieved simply by getting into the shoes of another. Conversation involves working to bring together the insights and questions of the different parties; it entails the fusion of a number of perspectives, not the entering into of one…”

I would add to this concern, a lack of acknowledgement in these “core conditions” of the unequal power relations in most educational encounters, and the lack of attention to the group processes in which the facilitator’s task may include that of mediating between conflicting interests.

Read through the eight aspects of a “person-centred mode” which are summarised in the extracts from Freedom to Learn (CLD3 2.4b) and think about the following questions in relation to your own experience as a student.

- Rogers represents “the awarding of grades and vocational opportunities” as a strategy for exercising power over learners. In choosing to follow an accredited course, are you a “mug” – the passive recipient from the “jug” of “factory knowledge”?

- Who makes these “top-down” decisions about what you should learn in order to practice as an informal/community educator and youth worker?

- Who is included in or excluded from making these decisions, and how?

- What changes would you like to see in this system, and how might you contribute to these changes?

Rogers does not attempt to analyse the structural issues that might help to illuminate these questions and suggest collective strategies for change. For example, professional qualifications serve a gate-keeping function in regulating who can call themselves a teacher, doctor, lawyer, counsellor or youth worker. Later in the book, Rogers describes various attempts to change educational institutions by bringing together staff and students at all levels of the hierarchy. Through the process of group discussion which Rogers and his colleagues initiated, the institutions were able to adopt more co-operative and democratic approaches to their work. But these institutions failed to sustain their internal democracy due to the interests of powerful groups in the wider society.

A school whose Black students and parents began to work together in democratic ways posed too great a threat to the existing political control of the surrounding White community. A Catholic college was closed after the Vatican discovered that nuns were making their own rules. Rogers acknowledged that real participatory democracy is an enormously challenging process. In his analysis of the “Reasons for Impermanence” of so many democratic and person-centred projects, Rogers stresses the lack of experience of this process among bureaucrats and administrators and fear of losing control which accounts for their hostility towards person-centred organisations.

The “fully functioning person” as an educational goal

I would argue that another “reason for impermanence” of these projects is that it’s just not enough to focus exclusively on process without offering tools for analysis and strategies for action. The goal of education, for Rogers is simply to promote the development of the “Fully Functioning Person” who will be equipped to continue striving for a more human world:

The only man who is educated is the man who has learned how to learn; the man who has learned how to adapt and change; the man who has realised that no knowledge is secure, that only the process of seeking knowledge gives a basis for security. Changingness, a reliance on process rather than upon static knowledge, is the only thing that makes any sense as a goal for education in the modern world. [Rogers,1983:120]

The modern world to which Rogers refers has become one in which it is very much in the interests of free-market enterprise to foster qualities and processes of “changingness” and flexibility (see, for example, Klein, 2008). The flexible movement of capital and labour, through flexible organisations which can adapt their products and services to gain advantage in rapidly changing markets, is supported by a flexible workforce of self-directing, “enterprising” individuals (Du Gay, 1996). A flexible, student-centred learning process is ideal for the production of such a workforce, willing to work flexible hours for flexible pay, to be downsized, upskilled or relocated in the service of the global corporation. Humanistic approaches to professional development and management training have provided an effective means for increasing productivity, but there is little evidence that this approach has led to more equal opportunities for participation in significant decision-making within or between the organisations of the workplace, the school or the public services.

When I began working in adult and community education in the 1970s, I welcomed Carl Rogers’ emphasis on the need to tune in to the experiences, interests and desires of learners in order to engage them fully in the learning process. This aspect of student-centred learning is influenced by John Dewey and shared by Paulo Freire. In the work of both Dewey and Rogers, however, the lack of attention to the role of the teacher or educator became problematic when political changes in the 1980s resulted in a shift in the meaning of student-centred learning. In the policy discourses of flexible learning, cost-effectiveness and the incorporation of business models into public sector organisations, student centred learning positioned the student as a customer in a supermarket of educational commodities or outcomes. The behaviourist framework of NVQs was presented in the language of freedom and individual choice (Jessup, 1991). The role of the educator as facilitator, in what Michael Collins (1994) described as a “cult of efficiency” was to offer advice and guidance to the bewildered customer in their choice of educational products (Clarke, 1993). In the context of adult education, Collins attributed this change to the influence of humanistic psychology on the work of Malcolm Knowles and the theory of andragogy.

Andragogy: a humanistic model for adult education?

We referred to the concept of andragogy in item 2 of this unit with reference to debates about the distinctive features of adult learners. In unit 1, item 3, we looked at changing ideas about individual and collective identities and contrasted the Enlightenment view of the “monological self”, with a Postmodern understanding of the “dialogical” or social self. I pointed out that:

Educational goals of autonomy and fulfilment, Erikson’s view of the development of individual identity, Maslow’s idea of self-actualisation, Carl Rogers’ notion of being “fully human” and Malcolm Knowles’ theory of andragogy are all rooted in modernist conceptions of the self (Clarke, 2010:2).

The problem with all these theories is that they don’t recognise and take account of the diverse experiences and social situations in which people may be and become adult human beings. Andragogy is a term used by Malcolm Knowles to define a theory of adult learning based on a particular set of assumptions about how adults learn. I hope that our discussion of Behaviourist and Humanist learning theories in this unit has equipped you with a critical eye to make your own evaluation of the theoretical basis for the theory of andragogy. I also hope that the items and Readings in unit 1: Critical theory for Critical Practice has suggested some alternative ideas and frameworks to guide an educational practice for social justice. In the final Reading with this item (CLD3 2.4c) Mark Smith explores Knowles’ ideas in relation to the work of both Carl Rogers and the pioneering adult educator, Eduard Lindeman.

Once again, Smith presents the arguments for and against Knowles’ claims, based on research conducted among mainly well-educated adults in North America, that all adults share particular characteristics as learners. For example:

… as an individual matures, his need and capacity to be self-directing, to utilise his experience in learning, to identify his own readiness to learn, and to organise his learning around life problems, increases steadily from infancy to pre-adolescence, and then increases rapidly during adolescence. (1978: 54)

This may certainly be true of some adults, in some situations. It may also be true of some children and young people in some situations. But the ways in which, and the extent to which, anyone directs their own learning, or uses their own experience for learning, depends on what kind of learning is going on, for what purpose, with whom and in what context. This is why it’s so important to consider the social context in which learning takes place, the cultural experiences, assumptions and expectations, and the relationship between educators and learners. We concluded item 2 with some questions about what an adult needs to learn in order to become an “authentic” self-directed learner. In the accompanying Reading, Stephen Brookfield points to the limitations of the humanistic concept of the self:

The self in a self-directed learning project is not an autonomous, innocent self, contentedly floating free from cultural influences. It has not sprung fully formed out of a political vacuum. It is, rather, an embedded self, a self whose instincts, values, needs and beliefs have been shaped by the surrounding culture. As such, it is a self that reflects the constraints and contradictions, as well as the liberatory possibilities, of that culture. The most critically sophisticated and reflective adults cannot escape their own autobiographies. Only with a great deal of effort and a lot of assistance from others can we become aware of how what we think are our own wholly altruistic impulses, free from any bias of race, gender or class, actually end up reinforcing repressive structures. Hence, an important aspect of a fully adult self-directed learning project should be a reflective awareness of how one’s desires and needs have been culturally formed and of how cultural factors can convince one to pursue learning projects that are against one’s own best interests (Brookfield 1994:7).

The final item in this unit will explore theories of learning which recognise the central importance of social context and collective learning processes.

References

Brookfield, S. (1994) Self-directed learning, CLD3 2.2d YMCA George Williams College.

Clarke, J. (1993) Unpacking student-centred learning, unpublished MA dissertation, Southampton University (available from the George Williams College library).

Clarke, J. (2002) Deconstructing Domestication: women’s experience and the goals of critical pedagogy in Harrison, Roger et al (eds) Supporting lifelong learning Volume 1: perspectives on learning, Routledge/Falmer (This chapter is included among the readings for CLD3 Unit 1, Item 2).

Collins, M. (1994) Adult Education as Vocation, Routledge.

Du Gay, P. (1996) Consumption and identity at work. London: Sage.

Freire, P. (1972), Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Penguin.

Grimshaw, J. (1986) Feminist Philosophers: women’s perspectives on philosophical traditions, Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Jessup, G. (1991) Outcomes: NVQs and the emerging model of education and training, Routledge.

Klein, N. (2008) The Shock Doctrine:The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, Random House.

Monbiot, G. (2006) Heat: How to Stop the Planet Burning, Allen Lane. Richards, B. Against Humanistic Psychology in Self and Society, 2, 1974. Rogers, C. (1978) Carl Rodgers on Personal Power: Inner Strength and Its Revolutionary Impact, Constable, London.

Rogers, C. and Freiberg, H. J. (1994) Freedom to Learn (3rd edition) Macmillan.

Smith, M. K. (1997, 2004) ‘Carl Rogers and informal education’, the encyclopaedia of informal education. [www.infed.org/thinkers/et-rogers.htm.

Images

(These links are to images used in the pdf version)

Maslow’s hierarchy http://idlichutney.blogspot.com/2008/12/i-need-to-know.html

Scientific inquiry http://ez002.k12.sd.us/Introduction%20Science.htm

Encounter group http://www.searchviews.com/wp-content/themes/clean-copy-full-3-column-1/images/group-therapy.jpg